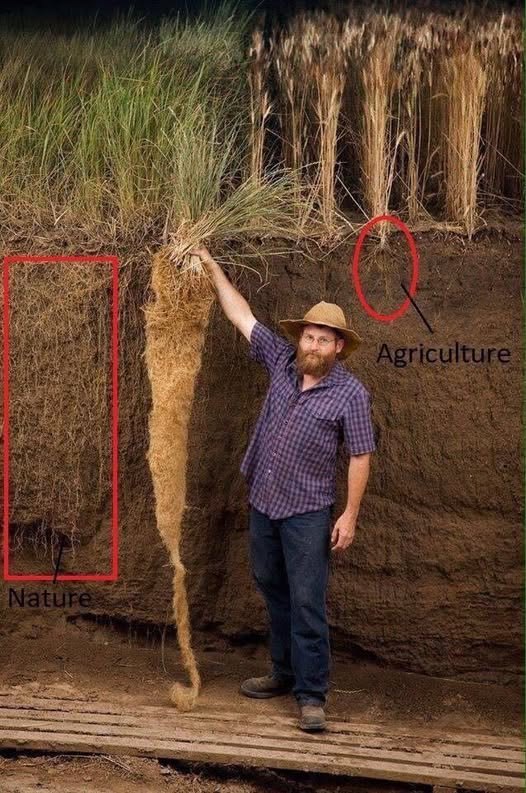

When comparing nature and agriculture, it might seem like they are fundamentally at odds—one thriving in wild, untamed balance, and the other rooted in human control, order, and productivity. But a closer look, especially starting from the ground up, reveals that these two systems are more interconnected than we might think. This becomes particularly clear when examining their roots—literally. A powerful visual comparison between the root system of native prairie grass and a typical agricultural crop tells a deeper story.

Prairie grasses, with their deep and extensive root networks, anchor the soil, retain water, prevent erosion, and help sustain biodiversity. Agricultural crops, in contrast, often have shallow roots, leaving the land more vulnerable to environmental stresses. This contrast played out dramatically in the early 20th century. When vast expanses of prairie in the U.S. were plowed for farming, deep-rooted native grasses were replaced with shallow-rooted crops. Then, when drought struck in the 1930s, the land couldn’t hold itself together, leading to the Dust Bowl—one of the most devastating environmental disasters in American history. It was a stark lesson in how removing nature’s foundational elements for short-term agricultural gain can have long-lasting, catastrophic consequences. Nature, when left alone, is an extraordinary self-sustaining engineer.

In wild ecosystems like meadows, forests, and wetlands, biodiversity thrives. Each plant, insect, and microorganism plays a role in keeping the system in balance. These natural communities promote resilience and adaptability. Without the need for human intervention, they attract pollinators, suppress pests, and regenerate themselves season after season. Agriculture, however, involves intentional intervention. To grow specific crops or raise certain animals, we often manipulate the land—tilling soil, managing water through irrigation, and applying fertilizers and pesticides. While these methods can boost productivity, they also risk depleting soil nutrients, polluting waterways, and reducing biodiversity if not carefully managed.

The conflict becomes most evident in industrial agriculture, which prioritizes high yields and efficiency. Monoculture—planting one type of crop across large areas—may simplify farming but strips the land of diversity and resilience. Over time, such practices can weaken the soil, reduce its ability to hold water, and increase dependence on chemicals. It’s a system that treats the land as an expendable resource rather than a living partner. But this doesn’t have to be the case. A growing movement known as regenerative agriculture seeks to bridge the divide between nature and modern farming.

This approach emphasizes rebuilding soil health, mimicking natural processes, and enhancing ecosystem services. Practices like crop rotation, cover cropping, reduced tillage, and agroforestry not only improve soil structure and fertility but also support wildlife and carbon sequestration. Regenerative agriculture turns farming into a restorative activity, where working with the land becomes more beneficial than working against it. By studying how natural ecosystems function, regenerative farmers create resilient systems that can better withstand droughts, pests, and climate changes. It’s a model that learns from the past—specifically, from the roots. The root systems of native plants are more than just support structures; they’re lifelines that sustain ecosystems from the ground up. By mimicking these systems in agriculture, we can nurture soil health, improve water retention, and create more sustainable food systems. The ultimate takeaway is that nature and agriculture aren’t enemies. They can complement one another, but it requires respect for nature’s methods and an understanding of the long-term consequences of disrupting them. Rather than choosing one over the other, we must find a way to let both thrive. When we look to the roots—those literal foundations beneath our feet—we find lessons in resilience, cooperation, and sustainability. The future of farming doesn’t have to come at the expense of the environment. By working with nature rather than against it, we can build a world where crops grow abundantly, ecosystems flourish, and the land continues to sustain generations to come.